43739.

Man with shotgun, boy with dog.

One of a collection of twenty-six stereographs (I have 4) from a series published by Fred S. Crowell titled “The Whiskey Crusade in Ohio.” The images document the activities of women who participated in the Temperance Crusade of 1873 – 1874 in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

One of a collection of twenty-six stereographs (I have 4) from a series published by Fred S. Crowell titled “The Whiskey Crusade in Ohio.” The images document the activities of women who participated in the Temperance Crusade of 1873 – 1874 in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

One of a collection of twenty-six stereographs (I have 4) from a series published by Fred S. Crowell titled “The Whiskey Crusade in Ohio.” The images document the activities of women who participated in the Temperance Crusade of 1873 – 1874 in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

No. 602. President Lincoln and Gen’l McClellan at Headquarters Army of the Potomac, Antietam, 4th October, 1862.

602. President Lincoln and Gen. McClellan in McClellan’s Tent at Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, Antietam, Oct. 4, 1862.

Frederick Swartwout Cozzens (1818-1869), American humorist who sometimes wrote under the pen name Richard Haywarde. Cozzens was born in New York City on 5 March 1818. In early life, he became a wine merchant. Beginning in 1854, he was the proprietor and editor of Cozzens’ Wine Press, a magazine on the culture of wine. In its issues, which he ran until 1861, he particularly promoted American wines. Cozzens had previously contributed humorous poems and articles to magazines, and in 1853 he issued his first volume, Prismatics, under the pen name “Richard Haywarde.” Then came The Sparrowgrass Papers, first published in The Knickerbocker, and collected in book form in 1856. The book, which was immediately popular and also published under the name Haywarde, followed a family that moved from New York City to the countryside in Yonkers. Three years later (1859) he published a volume of travel sketches, Acadia; or a Sojourn among the Blue Noses. The book reported on the difficulties of blacks who settled in Nova Scotia along the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Soon after the Civil War he failed in a business for which he had labored earnestly, especially by promoting the sale of native wines, and retired from Yonkers to Rahway, New Jersey. His other works include Poems (1867) and a Memorial of Fitz-Greene Halleck (1868). He was married with Susan (Meyers) Cozzens and was the father of the marine artist Fred S. Cozzens (1846-1928). Died 23 December 1869 on a visit to Brooklyn, New York.

Prominent Portraits No. 3878. Lieut. Gen’l Ulysses S. Grant, Com. in Chief Armies of the U.S.

Prominent Portraits No. 3877. Lieut. Gen’l Ulysses S. Grant, Com. in Chief Armies of the U.S.

Hindoo Dancing Girls.  From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

A Parsee Servant.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

The Hindoo Bangle-Seller.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

The Indian Ton-Ton.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

The Indian Cheetah.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

The Bheastie, or Water-Carrier.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

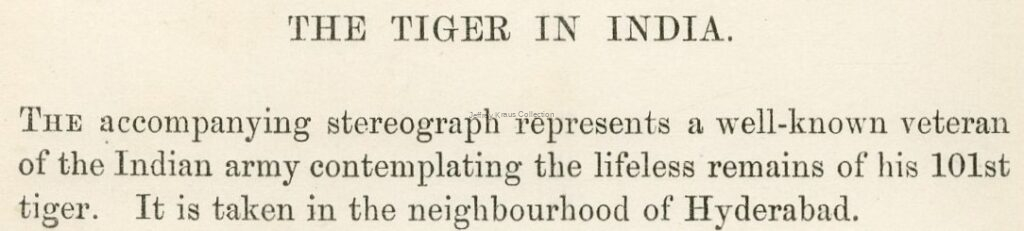

The Tiger in India.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

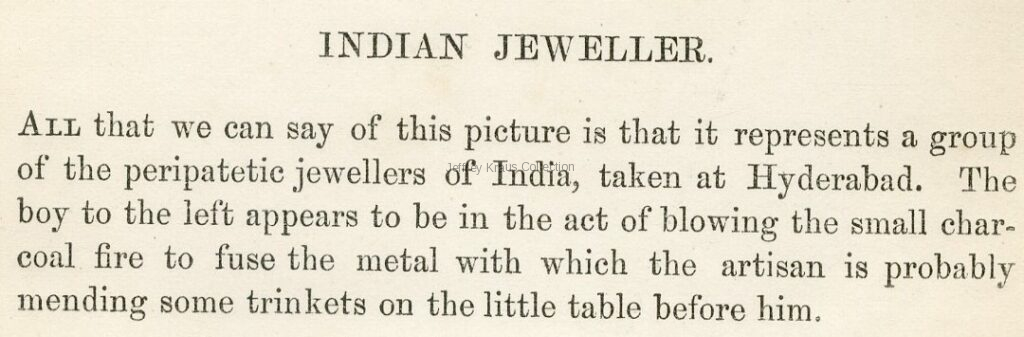

Indian Jeweller.

From The Stereoscopic Magazine, 1865, published by Lovell Reeve & Co., London.

Family group posed in front of folk-art painting of two children. Chess pieces on floor in front. Couple with game table at left.

One of a collection of twenty-six stereographs (I have 4) from a series published by Fred S. Crowell titled “The Whiskey Crusade in Ohio.” The images document the activities of women who participated in the Temperance Crusade of 1873 – 1874 in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

Front row on floor: Fred Lightfoot, Jim Klar, Jerry Slutzsky; Rear row: Margaret Lightfoot, Linda Slutzsky, Margaret Klar.

The Statue of Wm. Penn crowned by Fred’k Coombs. Frederick Coombs (sometimes Willie Coombs and also known as George Washington II) was an eccentric who lived in San Francisco in the 19th century and believed himself to be George Washington. For a time he was as popular a figure as Joshua A. Norton, the “Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico”, and his deeds were reported in the local newspapers. He left the city after a feud with Norton, who he thought was jealous of his “reputation with the fairer sex” and moved to New York City. Little is known of his early life. According to his own account, he was born in England in 1803. Coombs was apparently a phrenologist by trade, though he was also an accomplished photographer, daguerreotypist, inventor, and possibly a marriage broker. He had travelled throughout the west during the 1830s giving demonstrations of phrenology, apparently accompanied by a giant and a dwarf, and published at least one book on the subject, 1841’s Popular Phrenology, in which the features of George Washington’s skull are praised on the introductory page. He was interested in railways and designed a type of electric locomotive that enjoyed some minor success as a curiosity but was never put into large scale production. In 1848 he visited England where he obtained some commissions for the use of his engine, and claimed to have received a proposition to supply his engine to the Russians. He spent five years in England before returning to the United States.

Coombs was active as a photographer in the 1850s on the West Coast. Some time before 1863 he appeared in San Francisco, either claiming to be George Washington from the outset, or by other accounts, setting up his phrenology business and entertaining fashionable society with readings of their skulls. According to this second story, he was generally known as “Professor” Freddy Coombs and resembled George Washington so much that after many comments, he became convinced that he was the former President of The United States and took to dressing in uniform.

He wore a Continental Army uniform of tanned buckskin, and set up his headquarters at the saloon of Martin and Horton, where he would study maps while planning his campaigns for the Revolutionary War. He was reported to have spent a winter starving himself until he was convinced by concerned friends that the Battle of Valley Forge was over. In his office as President he composed letters to the United States Congress and issued proclamations, just as Norton did.

During the day he would often be seen in Montgomery Street wearing a powdered wig and tricorne hat and carrying a banner proclaiming himself “The Great Matrimonial Candidate”. Initially he, Norton, and the two well-known stray dogs Bummer and Lazarus drew equal interest from the San Francisco newspapers who delighted in recounting their exploits. Coombs appears in a couple of satirical cartoons by Edward Jump alongside Norton and the dogs: in Ambling along Montgomery Street he appears in the centre of the picture in full uniform holding a banner with the words “And Still They Go Marching On”, while in The Funeral of Lazarus he features as the gravedigger while Norton performs the ceremony.

Although short, balding, and rotund, Coombs was pompous and vain, and thought himself to be a ladies’ man. He believed this formed the basis of his dispute with Emperor Norton. Norton had torn down some posters that Coombs had put up in Montgomery Street and Coombs reported him to the police. As it was not a criminal offence the police told him they could do nothing, so in an attempt to raise funds for a civil action he sold his story to the Alta California newspaper. When the reporter asked him why Norton would have done such a thing Coombs replied that he “was jealous of my reputation with the fairer sex”. This caused great amusement and a few days later the Alta California published a story mocking both the men in which they reported that the “light of insanity” could be seen in Coombs’s eyes. Norton and Coombs, both convinced of their sanity, demanded a retraction, but Norton also issued his own proclamation against Coombs in which he ordered the Chief of Police to:

[…] seize upon the person of Professor Coombs, falsely called Washington No. 2, as a seditious and turbulent fellow, and to have him sent forthwith, for his own good and the public good, to the State Lunatic Asylum for at least thirty days.

Coombs left the city immediately, presumably for New York, as in 1868 he was discovered there by Mark Twain, still believing himself to be Washington and still convinced of the effect of his charms on the ladies, whom he entertained by displaying his legs on street corners. Twain reported that he travelled around New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington selling photos of himself visiting Benjamin Franklin’s grave for 25 cents. When the William Penn Mansion in Philadelphia was proposed for demolition he asked Congress to give it to him. After it was torn down he switched to demanding the Washington Monument.

Coombs died in New York City on April 9, 1874.